What Not to Do

When you interact with someone on the spectrum, chances are they'll be very accommodating of you (and here you thought it was the other way around!). They'll probably patiently answer any questions or endure any blunders you may make without saying anything. That said, certain things cross the line from easy to ignore slip ups into actually offensive territory. Here are some hot button things to avoid saying or doing around a person on the spectrum. The video is a humorous take on several common mistakes (my apologies for the cursing in the title) and we'll go more in depth with the others later in the article.

Things to Avoid Asking/Saying

"I thought people with autism were retarded."

First of all, way to use a seriously offensive word. You should remove it from your vocabulary. Secondly, there are three ways to interpret this statement:

1. You're questioning the person's diagnosis.

2. You're questioning the person's intelligence.

3. Your own intelligence is to be questioned because you said this.

None of these interpretations end well for your interaction.

1. You're questioning the person's diagnosis.

2. You're questioning the person's intelligence.

3. Your own intelligence is to be questioned because you said this.

None of these interpretations end well for your interaction.

"Are you a savant?"

As discussed in Myths, odds are high that the person is not. For those 9/10 people, this question can be offensive as it may make them feel that they're failing both society's expectation of someone 'normal' and its expectation of someone on the autism spectrum.

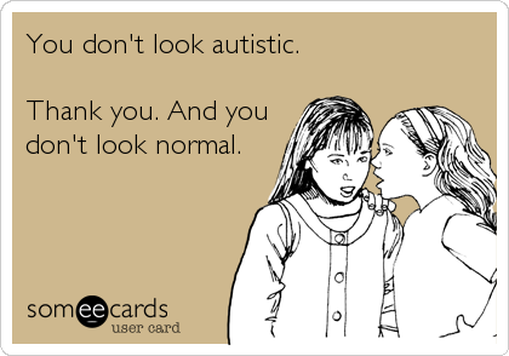

"You don't look autistic."

I think this picture does all the explaining for me:

This isn't the compliment people seem to think it is.

"Oh, yeah, autism - isn't that caused by _____?"

Causes are incredibly controversial and, speaking simply from what I've seen, don't seem to be entertained as readily by people on the spectrum themselves, meaning they're an even trickier subject to navigate. I don't know what you're going to fill in that blank with, but if you have to ask chances are it's not right and this question is better left avoided.

"You can talk for yourself, but what you have to say doesn't apply to people who can't communicate."

Stop and think before you conclude this. My sister has run into this multiple times (and, indeed, it's an oft-used argument against the neurodiversity movement), but no time has it been true. This argument is way overused as a way to easily get rid of challenging views coming from people on the spectrum.

For example, when my sister was advocating against certain controversial treatments with a parent, they came at her arguing that her thoughts didn't count because they were arguing on behalf of their nonverbal child, not "people who could use social media like [my sister]." In the end it turns out their child was the ripe old age of four, already had a limited vocabulary, and would probably use social media just as well as my sister when he/she entered adulthood. That argument was dead on arrival. (And would be dead either way because not being able to speak and not being able to use social media are not the same thing and the mother should not have assumed that Caley was 'verbal' just because she was able to type online.)

Moreover, even in cases of actual adults on the spectrum who can't communicate, others on the spectrum are likely to have a different perspective which bears real consideration. In addition, if the inability to communicate is the crux to being able advocate for people who can't, both sides in this argument lose simply by virtue of the fact that they're capable of having an argument.

The advice of people on the spectrum cannot and should not be summarily dismissed with a stock argument such as this one. They have some great insights that neurotypical people don't; take their words into consideration before you wave them off.

For example, when my sister was advocating against certain controversial treatments with a parent, they came at her arguing that her thoughts didn't count because they were arguing on behalf of their nonverbal child, not "people who could use social media like [my sister]." In the end it turns out their child was the ripe old age of four, already had a limited vocabulary, and would probably use social media just as well as my sister when he/she entered adulthood. That argument was dead on arrival. (And would be dead either way because not being able to speak and not being able to use social media are not the same thing and the mother should not have assumed that Caley was 'verbal' just because she was able to type online.)

Moreover, even in cases of actual adults on the spectrum who can't communicate, others on the spectrum are likely to have a different perspective which bears real consideration. In addition, if the inability to communicate is the crux to being able advocate for people who can't, both sides in this argument lose simply by virtue of the fact that they're capable of having an argument.

The advice of people on the spectrum cannot and should not be summarily dismissed with a stock argument such as this one. They have some great insights that neurotypical people don't; take their words into consideration before you wave them off.

"I know all about autism because my [fill in the blank extended family] has it!"

I once met three separate people with elementary-school aged autistic cousins in the space of one week. Not a single one of them had a clue about autism, but they all tried to use their relationship as a trump card to demonstrate their superior knowledge (and were all cowed when I revealed I had an Autistic sister - apparently sister trumps cousin?). There are so many things wrong with this, so I'm going to take them on one at a time.

First, I can personally attest that having a relative (even a first degree relative, like a sibling or child, let along a second degree one) on the spectrum does not mean you understand it. I didn't grasp my sister's autistic traits until she'd been around almost two decades, and that was thanks only to an intense concerted research effort on my part rather than simple osmosis. To be honest, the people I have met with the most misconceptions about autism have been, in fact, relatives who know just enough to be dangerous, but not enough to actually understand. So, no, that is not a trump card.

Second, you really can't claim to understand all autistic age groups if you've only seen one age group. So if you've only known an older person, you might not understand children on the spectrum as well, and vice versa. You've seen one age group, but autistic people do mature and grow over time. Many of the basic understandings you may have gained from a relative who is a young child may simply not apply to older children, let alone adults, and vice versa (although that happens less frequently).

Finally, you can't generalize from one person. The saying goes, if you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person. That's it.

I'm not saying relatives can't have a good understanding of autism. All I'm saying is that odds are they learned much of what they know from research sparked by their extended relative, not simply by virtue of being related, despite what is so often implied.

First, I can personally attest that having a relative (even a first degree relative, like a sibling or child, let along a second degree one) on the spectrum does not mean you understand it. I didn't grasp my sister's autistic traits until she'd been around almost two decades, and that was thanks only to an intense concerted research effort on my part rather than simple osmosis. To be honest, the people I have met with the most misconceptions about autism have been, in fact, relatives who know just enough to be dangerous, but not enough to actually understand. So, no, that is not a trump card.

Second, you really can't claim to understand all autistic age groups if you've only seen one age group. So if you've only known an older person, you might not understand children on the spectrum as well, and vice versa. You've seen one age group, but autistic people do mature and grow over time. Many of the basic understandings you may have gained from a relative who is a young child may simply not apply to older children, let alone adults, and vice versa (although that happens less frequently).

Finally, you can't generalize from one person. The saying goes, if you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person. That's it.

I'm not saying relatives can't have a good understanding of autism. All I'm saying is that odds are they learned much of what they know from research sparked by their extended relative, not simply by virtue of being related, despite what is so often implied.

"Do you have emotions?"

This should be a gimme. I don't care where on the spectrum the person is that you're talking to, yes, they have emotions. Questioning that can be seen as questioning their humanity and rather offensive.

Things to Avoid Doing

Ignoring their opinion.

It is saddening the differences between the respect people give to my opinions as opposed to my sister's. We aren't that different - in fact, many have pointed out how similar we are. Yet when it comes time to have our opinions considered, over and over people value my own above hers, even if the two of us have equal backgrounds in the domain at hand.

I remember my sister gave her opinion about an issue once, which was the same opinion as my own, albeit presented with more passion. The reaction she got was intense as three people simultaneously moved to shoot her down. In that moment, I realized that if the same exact words had come out of my mouth, they would have been seriously considered. Because they came from my sister's, though, they were automatically discounted. Don't fall into this trap. People on the spectrum's opinions are just as valuable as yours or mine and deserve your respect. Judge their opinions for their words, not the stigma associated with their diagnosis.

I remember my sister gave her opinion about an issue once, which was the same opinion as my own, albeit presented with more passion. The reaction she got was intense as three people simultaneously moved to shoot her down. In that moment, I realized that if the same exact words had come out of my mouth, they would have been seriously considered. Because they came from my sister's, though, they were automatically discounted. Don't fall into this trap. People on the spectrum's opinions are just as valuable as yours or mine and deserve your respect. Judge their opinions for their words, not the stigma associated with their diagnosis.

Doubting their autism.

Obviously, doubting the person's diagnosis (which can be seen as doubting a part of their identity) is not a good way to go. They've been diagnosed by a professional and it's not your place to question that.

More commonly, however, I run into cases where people don't doubt the diagnosis, but doubt that certain traits are due to autism. I've hit most of those already in Specific Traits, but for those I couldn't get to, know that the range of traits that people with autism possess is incredibly large and diverse. Don't doubt them when they won't wear that scratchy sweater Grandma knitted them, or insist on leaving the lights off in the room and say it's because of their autism. If they say it is, that's probably the case; they know better than we do.

More commonly, however, I run into cases where people don't doubt the diagnosis, but doubt that certain traits are due to autism. I've hit most of those already in Specific Traits, but for those I couldn't get to, know that the range of traits that people with autism possess is incredibly large and diverse. Don't doubt them when they won't wear that scratchy sweater Grandma knitted them, or insist on leaving the lights off in the room and say it's because of their autism. If they say it is, that's probably the case; they know better than we do.

Talking about the person like they aren't there, directing questions to caregivers/adults instead of a competent autistic individual, etc.

This should be pretty self-explanatory. Even if a person is non-speaking, that doesn't mean they should be ignored and odds are quite high that they understand what you're saying. Watch your words because, as stated above, autistic people have emotions and they can most definitely be hurt.

In response to the second half, directing of questions, etc to caregivers or non-autistic adults, you're basically telling the person with autism that you regard their opinion as worth less than a non-autistic person and that they don't matter to you. Feeling like no one cares what they have to say is a problem that plagues many people with autism, simply because too few people do. Step into the autistic person's shoes and ask yourself how you'd feel if people ignored you. Chances are you wouldn't like it.

Treat others the way you would like to be treated.

In response to the second half, directing of questions, etc to caregivers or non-autistic adults, you're basically telling the person with autism that you regard their opinion as worth less than a non-autistic person and that they don't matter to you. Feeling like no one cares what they have to say is a problem that plagues many people with autism, simply because too few people do. Step into the autistic person's shoes and ask yourself how you'd feel if people ignored you. Chances are you wouldn't like it.

Treat others the way you would like to be treated.

Treating the person like a child or otherwise infantilizing them.

Naturally, treating someone like a child is okay if they actually are one (although I'd stop that when they hit adolescence). However, an autistic adult is just that, an adult. There's no need to use a baby voice, speak more slowly, or anything of the sort. For an example of infantilization of an autistic person, I can think of no better example than the clip below (which was also displayed in the Narrative article; if you didn't watch it then, you should watch it now!).

My Sister's Input

Though I based the above advice on my sister's experiences and she wholeheartedly agreed with what I wrote, she felt certain issues still needed addressing. Here are her additional points:

- Even if you think someone's going to feel a certain way because they're autistic, you should ask them anyway. Autism doesn't make someone predictable enough to mean you should stop asking their opinion.

- Don't exclude people on the spectrum.

- Don't correct or try to educate the other person on social norms unless they've asked for it, or otherwise communicated they're okay with it.

- Even if you think someone's going to feel a certain way because they're autistic, you should ask them anyway. Autism doesn't make someone predictable enough to mean you should stop asking their opinion.

- Don't exclude people on the spectrum.

- Don't correct or try to educate the other person on social norms unless they've asked for it, or otherwise communicated they're okay with it.

A Summary of What Not to Do

I wrote this article - and then found another on a different website which took many of the underlying problems behind my points and addressed them. I highly recommend reading it. Here's a preview:

"This is what infantilization means: treating autistic adults without the respect accorded to any other adult. It means dismissing their opinions, comparing them to children, invading their privacy, perceiving them as in need of an authority's protection and control, believing they are not competent to comprehend other autistic children's situations, and seeing them as not competent to make decisions for themselves, other autistic persons, or children."

Agree or disagree with it, the author makes some excellent points which go beyond the basics I've covered and challenge many attitudes towards people on the autism spectrum. You can read the rest of the article here.

"This is what infantilization means: treating autistic adults without the respect accorded to any other adult. It means dismissing their opinions, comparing them to children, invading their privacy, perceiving them as in need of an authority's protection and control, believing they are not competent to comprehend other autistic children's situations, and seeing them as not competent to make decisions for themselves, other autistic persons, or children."

Agree or disagree with it, the author makes some excellent points which go beyond the basics I've covered and challenge many attitudes towards people on the autism spectrum. You can read the rest of the article here.