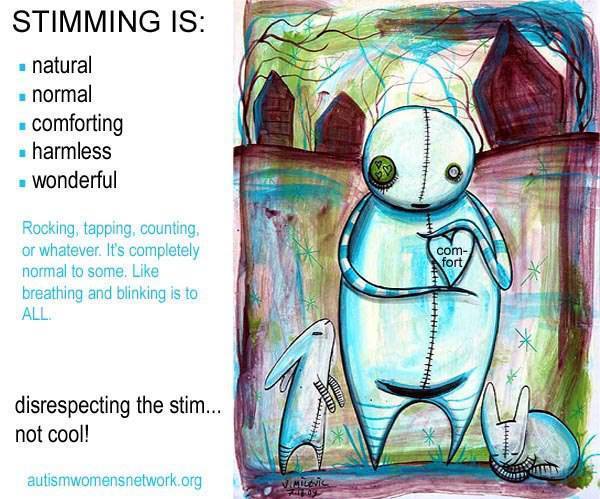

I will also often use the stims I see as an indicator of the person's internal state when they're not talking. After all, behavior is communication, and if I see a bunch of stimming that seems to 'stem' from something negative, I will get concerned and try to help minimize the negative problem. But it is not the stimming that concerns me, but rather the internal state it can sometimes be a communicator of. And if I see happy stims, like the joyous flapping of hands after defeating a video game level or when reading a particularly great fanfiction, that fills me with joy, not concern.

In short, stimming is not a negative thing.

-Creigh

RSS Feed

RSS Feed